Nvidia's growth engine has only one wheel

Nvidia has fallen into a strange cycle where slightly exceeding expectations is considered as not meeting expectations.

Written by: Li Yuan

Editor: Zheng Xuan

Source: GeekPark

On August 28, East 8th District time, Nvidia released its financial report for the second quarter of fiscal year 2026.

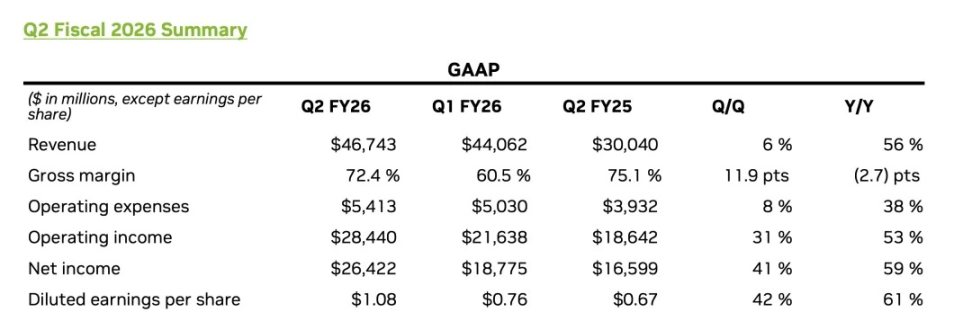

From a performance perspective, Nvidia once again delivered an outstanding report card:

- Second quarter revenue reached $46.743 billions, a year-on-year increase of 56%, slightly higher than the market's previous expectation of $46.23 billions;

- The core engine, data center business revenue, hit a new high at $41.1 billions, up 56% year-on-year;

- Adjusted earnings per share were $1.05, up 54% year-on-year, also exceeding expectations.

However, a seemingly perfect performance failed to fully reassure Wall Street.

The market reaction was direct and intense: Nvidia's after-hours stock price once plunged more than 5% (UTC+8). By the end of after-hours trading, the decline had narrowed to 3% (UTC+8), but the volatility itself already revealed a lot.

Nvidia is a particularly unique company in the current market: its absolute core business revenue comes from AI data centers, and this massive and rapidly growing data center revenue is also highly concentrated among a few "whale" clients, such as large cloud service providers and top AI model research institutions represented by OpenAI.

This revenue structure means that Nvidia's growth is deeply "tied" to the capital expenditures and AI strategies of these leading players. Any movement from them is directly transmitted to Nvidia's performance and market expectations. Nvidia's stock price is no longer a simple reflection of its own performance, but a barometer of confidence in the entire AI market.

Its extremely high valuation has already priced in the dream of "AI taking off," and the market has fallen into a cycle where "slightly exceeding expectations is not enough"—only overwhelming "big beats" can drive the stock up.

Deeper anxiety lies in the fact that the capital market's fundamental questioning of AI has never stopped: Is this computing power-driven revolution still in a stage where high investment is needed for early layout, or has it already reached the "cost reduction and efficiency improvement" accounting logic? No one knows the answer, but everyone fears the party could end at any time.

At the same time, uncertainties in the China business have also intensified this uncertainty. The financial report shows that Nvidia did not sell H20 chips to China in the second quarter, and the outlook for the third quarter does not include related revenue. Although Jensen Huang expressed long-term optimism about the Chinese market at the earnings call, stating that "the possibility of bringing Blackwell to the Chinese market is real," and estimated that the opportunity size in China this year could reach $50 billions, the short-term revenue gap is very real.

As the manager of this company standing at the top of the world, Jensen Huang is resolute: he has painted an extremely grand endgame for the future of Nvidia and the entire AI industry. At the earnings call, he clearly predicted that by the end of this decade, the annual expenditure on global AI infrastructure will reach $3 trillions to $4 trillions. What he sees is not just a quarter's worth of orders, but a decade-long, AI-driven new industrial revolution.

His confidence is also reflected in the fact that Nvidia returned $10 billions to shareholders this quarter and announced a new stock buyback authorization of up to $60 billions.

The expected growth for the next quarter is also solid: the third quarter revenue guidance of $54 billions means the company will once again create an astonishing incremental revenue of over $9.3 billions in just three months.

Although this guidance is slightly higher than Wall Street's consensus expectations, it is far below the $60 billions anticipated by some optimistic analysts. This intertwining of the market's eternal greed for "skyrocketing" and fear of slowing growth and external risks is precisely the biggest challenge Nvidia will face next.

01 The Future of Data Center Business: Chip Transition Relay + Agent AI

As the absolute core of the Nvidia empire, the data center business's performance this quarter perfectly illustrates the subtle gap between "excellent" and "market expectations."

From the data, the growth story continues.

- Overall revenue hit a new high: total data center business revenue reached $41.1 billions, up 56% year-on-year and 5% quarter-on-quarter.

- Blackwell engine in full swing: The new generation Blackwell architecture products began to be released in force, with data center-related revenue surging 17% quarter-on-quarter. The flagship product GB300 has entered full-scale mass production, reaching a pace of about 1,000 racks produced per week (UTC+8). The Blackwell Ultra platform has already become a "multi-billion dollar" product line this quarter, showing the market's extreme demand for the new architecture.

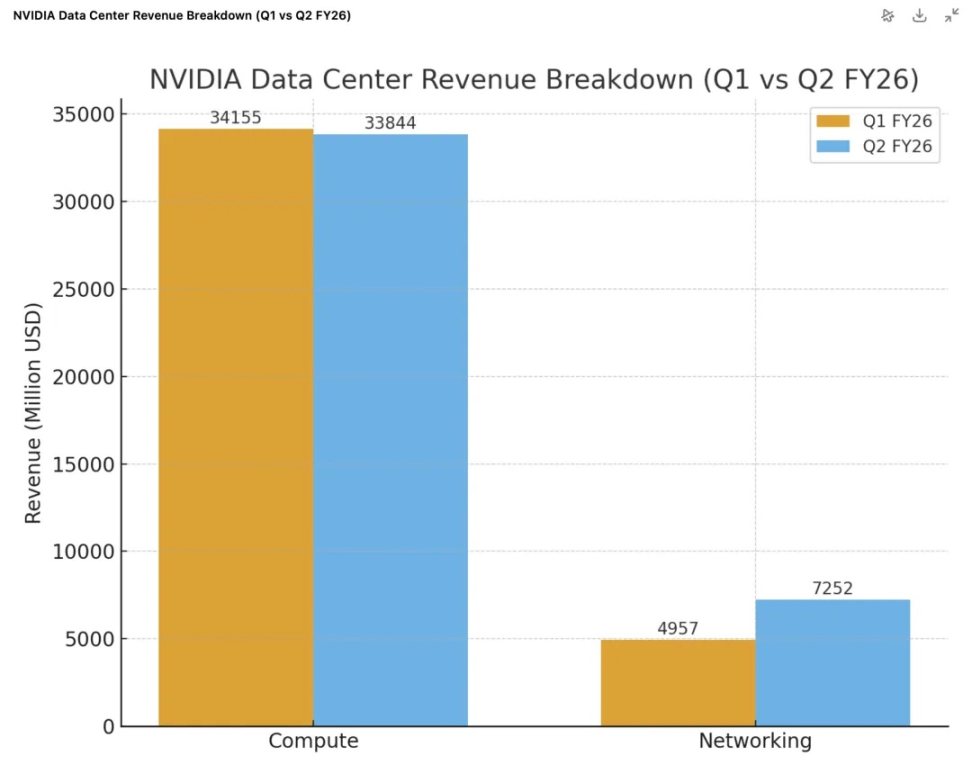

- Networking business becomes the "second engine": This quarter, the networking business performed exceptionally well, with revenue reaching $7.3 billions, a year-on-year increase of 98% and a quarter-on-quarter increase of 46%. The AI-optimized Spectrum-X Ethernet business has achieved an annualized revenue exceeding $10 billions.

- Emerging markets rising rapidly: "Sovereign AI" is becoming a significant growth point, and Nvidia expects revenue in this field to exceed $2 billions this year, more than double last year's figure.

However, under the market's magnifying glass, there are "flaws" in this report card that make investors uneasy. First, the $41.1 billions in revenue was slightly below the market's previous expectation of $41.3 billions. However, this decline was mainly due to a $4 billions reduction in H20 chip sales to China, which is consistent with what happened in the first quarter.

Fortunately, the explosive growth of the networking business became a key highlight to offset GPU pressure. This quarter, networking business revenue reached $7.3 billions, a year-on-year increase of 98% and a quarter-on-quarter increase of 46%. This was mainly due to the hot sales of high-performance networking products such as NVLink and InfiniBand, which are tied to the Blackwell platform. These figures clearly show that Nvidia's success is no longer about selling standalone GPUs, but about selling a complete set of high-profit "AI factory solutions" that include high-speed interconnected networks.

The core issue behind the data is what the market cares about most: Can Nvidia maintain high-speed growth at such a massive scale?

In the current market structure, this is almost not a question of "competition." Jensen Huang made it clear at the earnings call that due to the rapid iteration of AI models and the extremely complex technology stack, Nvidia's general-purpose, full-stack platform has a huge advantage over dedicated ASIC chips, so external competitive pressure is not fatal.

Jensen Huang also emphasized the current core bottleneck in data center construction—electricity. When electricity becomes the core constraint on data center revenue, "performance per watt" directly determines the data center's earning power. This also explains why customers are willing and must purchase Nvidia's latest and most expensive chips annually. Each new architecture (from Hopper to Blackwell to Rubin) brings a huge leap in "performance per watt," and buying new chips is essentially a direct investment in the "revenue ceiling" under limited power resources.

The real pressure comes from the natural law of AI development—can AI development be sustained?

On this, Jensen Huang gave his answer: Reasoning Agentic AI.

He said at the earnings call:

"In the past, the interaction mode of chatbots was 'single trigger'—you give a command, it generates an answer; but now AI can autonomously conduct research, think, and make plans, even calling tools. This process is called 'deep thinking'... Compared to the 'single trigger' mode, the computing power required by reasoning agentic AI models may be 100 times, 1,000 times more."

The core logic of this statement is: when AI evolves from a simple "Q&A tool" to an "agent" capable of independently completing complex tasks, the required computing power will explode exponentially.

For investors, Nvidia's data center business story is already very clear and progressive: current growth is firmly taken over by the Blackwell platform; the next generation of growth is on the way—Jensen Huang announced at the earnings call that all six new chips of the next-generation Rubin platform have completed tape-out at TSMC and entered the wafer manufacturing stage, on schedule for mass production next year.

And the ultimate fuel driving this perpetual growth is entirely pinned on whether the market believes the "Agent AI" era will really arrive quickly as predicted and create endless demand for computing power.

02 About China: Geopolitical Impact Continues

At the earnings call, Jensen Huang once again reiterated his long-term confidence in the Chinese market. He estimated that "China could bring the company $50 billions in business opportunities this year, with an annual market growth rate of about 50%," and clearly expressed his desire to "sell newer chips to the Chinese market."

The blueprint is optimistic, but the financial reality is harsh.

As the core engine contributing over 88% of revenue, Nvidia's data center business grew 56% year-on-year this quarter, but its $41.1 billions in revenue was slightly below analysts' expectations of $41.29 billions. This is the second consecutive quarter that this business has failed to meet Wall Street expectations.

The problem lies in the China business. Further breakdown of the data center business shows that its core GPU computing chips achieved revenue of $33.8 billions, down 1% quarter-on-quarter. The direct reason for this decline is that the H20 "special edition" chips for the Chinese market had zero sales to China this quarter, resulting in a revenue gap of about $4 billions.

To understand this gap, we must review the policy changes over the past two quarters:

First Quarter: Policy "Sudden Brake"

- In April this year, the US government required that H20 chip exports to China must obtain prior licenses, which almost instantly "choked" Nvidia's H20 in the Chinese market.

- Facing a large backlog of inventory and related contracts prepared for the Chinese market, the company had to make a $4.5 billions loss provision. At the same time, $2.5 billions in signed orders could not be delivered due to the new regulations.

- Nevertheless, Nvidia managed to ship $4.6 billions worth of H20 chips to China before the restrictions took full effect. Although this "last train" sale was one-off, it greatly boosted the first quarter's computing business revenue base.

Second Quarter: Revenue "Vacuum Period"

- In the second quarter, H20 sales to China dropped to zero.

- However, Nvidia found some new customers outside China and successfully sold $650 millions worth of H20 inventory. As these goods were sold smoothly, the company was able to reverse $180 millions in previously accrued risk reserves back into profit.

- But overall, H20 chip-related revenue still dropped by about $4 billions compared to the first quarter. This explains why computing business saw a 1% quarter-on-quarter decline in the second quarter—because it is being compared to a first quarter that included a "one-off" high income.

Currently, the US government's export restriction policy on AI chips remains unclear. Previously, the Trump administration proposed requiring companies like Nvidia and AMD to hand over 15% of their chip sales revenue to China, but this policy has not yet become formal regulation.

It is precisely because of this uncertainty that Nvidia has taken the most conservative stance in its official guidance—its third quarter revenue estimate of $54 billions explicitly counts H20 revenue from China as zero. However, CFO Colette Kress also gave a statement with potential upside. She revealed that the company is "waiting for the White House's official regulations," and also said: "If the geopolitical environment allows, third quarter H20 chip shipments to China could bring in $2 billions to $5 billions in revenue."

Whether it can sell to the Chinese market, when it can sell, and what it can sell, is not up to Nvidia itself, but hangs in the balance of geopolitics.

03 The Growth of Supporting Roles: Fast, but Hard to Support a Trillion-Dollar Valuation

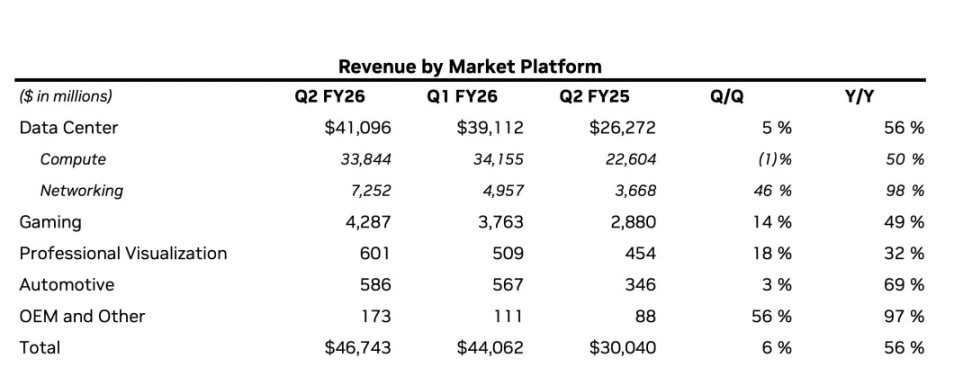

When all the spotlight is on the data center business, it's easy to overlook the growth of Nvidia's other business segments. In fact, if you look at them individually, each one is a pretty good report card.

The gaming business is the brightest supporting role this quarter.

- This business achieved revenue of $4.3 billions, a year-on-year increase of 49% and a quarter-on-quarter increase of 14% (UTC+8), showing strong recovery momentum.

- The core driver of growth comes from new products: the GeForce RTX 5060 based on the Blackwell architecture quickly became the fastest-growing x60-level GPU in Nvidia's history upon launch, proving its strong appeal in the consumer market.

Professional visualization and automotive robotics businesses are sowing seeds for the future.

- Professional visualization business revenue was $601 millions, up 32% year-on-year. High-end RTX workstation GPUs are increasingly used in AI-driven workflows such as design, simulation, and industrial digital twins.

- Automotive and robotics business revenue was $586 millions, up 69% year-on-year. The most critical progress is that the DRIVE AGX Thor system-on-chip, regarded as the next-generation "supercomputer on wheels," has officially started shipping, marking the beginning of commercial harvest in the automotive sector (UTC+8).

- In addition, this quarter, its new generation robotics computing platform THOR was officially launched, with AI performance and energy efficiency achieving "orders of magnitude" improvement over the previous generation. Jensen Huang's logic is that the computing power demand for robotics applications on both the device side and infrastructure side (for training and simulation on the Omniverse digital twin platform) will grow exponentially, which will become an important driver of long-term demand for future data center platforms.

However, although the growth rates of these businesses are impressive, their scale is not in the same league as the data center business.

The gaming business's $4.3 billions in revenue is only one-tenth of the data center business. The combined revenue of professional visualization and automotive robotics is only about $1.2 billions, which can almost be regarded as "other income" compared to the $41.1 billions data center giant.

This leads to a clear conclusion: in the foreseeable future, none of Nvidia's "side businesses" can grow into a "second growth curve" that can rival the data center business. They are healthy and important businesses that build a richer ecosystem for the company and explore the application possibilities of AI at the edge and in the physical world.

But for a behemoth that needs hundreds of billions in revenue to support its multi-trillion-dollar market cap, the current contribution of these businesses is still far from enough to alleviate the market's "growth anxiety."

Nvidia's stock price fate remains firmly tied to the data center "chariot."