Controlled Decay: When Finance Becomes the Economy Itself

Everyone Lends, No One Invests: How Is Innovation Squeezed Out?

Written by: arndxt

Translated by: AididiaoJP, Foresight News

The market will not self-correct; the government once again becomes a key element in the production function.

The ultimate outcome may not be a collapse, but rather a controlled decline—a financial system that survives on reflexive liquidity and policy scaffolding, rather than productive reinvestment.

The U.S. economy is entering an era of managed capitalism:

- Stocks are pulling back

- Debt is dominant

- Policy has become the new driver of growth

- And finance itself has become the economic leader

Nominal growth can be manufactured, but real productivity requires restoring the connection between capital, labor, and innovation.

Without this, the system may be sustained, but it no longer generates compounding effects.

Structural Shift in Capital Composition

The stock market was once the core engine of American capitalism, but today it fails to systematically provide accessible capital for a broad range of U.S. companies. The result is a massive shift toward private credit, which now acts as the capital allocator in most middle-market and capital-intensive industries.

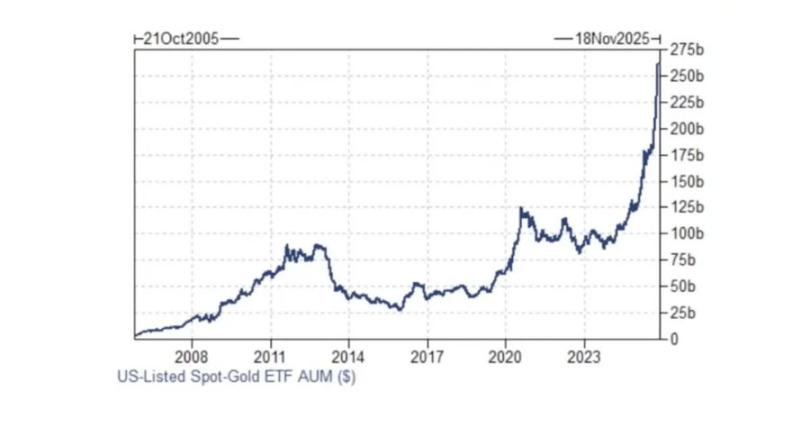

The volume of public stock offerings remains near multi-decade lows, while private debt assets under management have exceeded $1.7 trillion, mirroring the late stage of the financialization cycle. Companies increasingly prefer debt over equity, not because they have better credit, but because the public market structure is broken: low liquidity, concentration of passive investment, and punitive valuation multiples for asset-heavy business models make going public no longer the first choice.

This has created a perverse incentive loop: no one wants a balance sheet. Asset-light, rent-extracting business models dominate valuation frameworks, while capital-intensive innovation lacks equity funding. Meanwhile, private credit has embraced an “asset capture” model: lenders win in any outcome, earning high spreads in success and seizing hard assets in distress.

The Era of Financialization

This trend is the peak of a forty-year hyper-financialization experiment. As interest rates are structurally lower than growth rates, investors seek returns not through productive investment, but through financial asset appreciation and leverage expansion.

Key consequences:

- Households have replaced stagnant wage growth with ever-rising asset values.

- Companies prioritize shareholder supremacy, outsource production, and pursue financial engineering.

- Economic growth is decoupled from productivity, relying on asset inflation to sustain demand.

This dynamic of “debt with no productive use” has hollowed out the domestic industrial base and created an economy optimized for capital returns rather than labor returns.

Crowding Out Effect and Credit Reflexivity

The post-pandemic fiscal regime has exacerbated this problem. Record sovereign issuance has crowded out private borrowers in public credit markets, pushing capital into private lending structures.

Private credit funds now price loans based on artificially compressed public spreads, creating a reflexive feedback loop:

- Public issuance declines

- Forced buyers chase limited high-yield supply

- Spreads tighten

- Private credit reprices lower

- More issuance shifts to private

- Cycle reinforces itself

Meanwhile, since 2020, the Federal Reserve’s implicit support for corporate credit has distorted the informational value of spreads themselves; default risk is no longer priced by the market, but managed by policy.

The Problem with Passive Investing

The rise of passive investing has further undermined price discovery. Index-based fund flows dominate stock trading volumes, concentrating ownership in a handful of trillion-dollar asset management firms whose incentives are homogeneous and benchmark-constrained.

The result:

- Small and mid-cap listed companies suffer from structural illiquidity.

- Stock research coverage collapses.

- The IPO market shrinks, replaced by late-stage private funding rounds (Series F, G, etc.) inaccessible to public investors.

The breadth and vitality of the market have been replaced by oligopolistic concentration and algorithmic liquidity, resulting in volatility clusters when fund flows reverse.

Crowding Out Innovation

The homogeneity of finance is reflected in the real economy. A healthy capitalist system requires heterogeneous incentives: entrepreneurs, lenders, and investors pursuing different goals and time horizons. Instead, today’s market structure compresses risk-taking into a single dimension: maximizing returns under risk constraints.

Historically, innovation thrived at the intersection of diversified industries and capital structures. The collapse of this “everyone lends, no one invests” ecosystem is reducing serendipitous innovation and long-term productivity growth.

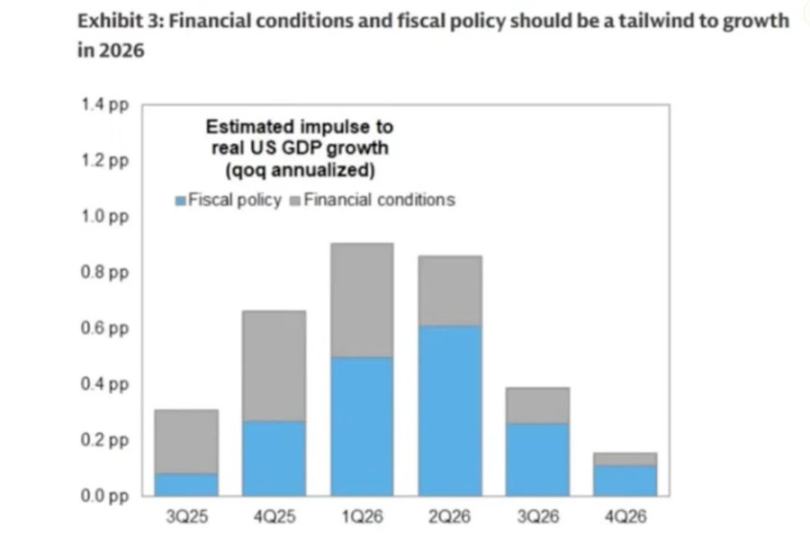

The Necessity of New Industrial Policy

As this structure erodes organic growth potential, the state is once again becoming a primary economic actor. From the CHIPS Act to green subsidies, fiscal industrial policy is being used to compensate for the failures of private capital.

This represents a partial inversion of the U.S.-China model: the U.S. now uses targeted public-private partnerships to re-anchor supply chains and create nominal growth, while China leverages state-owned enterprises and manufacturing to assert global dominance.

However, execution remains uneven, constrained by politics, resource inefficiency, and geographic mismatches (e.g., building semiconductor plants in water-scarce Arizona). Nevertheless, the philosophical shift is decisive:

Social Contract and Political Reflexivity

The consequences of forty years of financialization are reflected in the gap between asset wealth and wage income. Housing and stocks now account for a record share of GDP, while real wages stagnate.

If opportunities are not redistributed—not through transfer payments, but through ownership—political stability will be eroded. From tariffs to industrial nationalism, the rise of populist and protectionist movements is a symptom of economic disenfranchisement. The U.S. is not immune; it is leading this experiment.

Outlook: Stagnation, State Capitalism, and Selective Growth

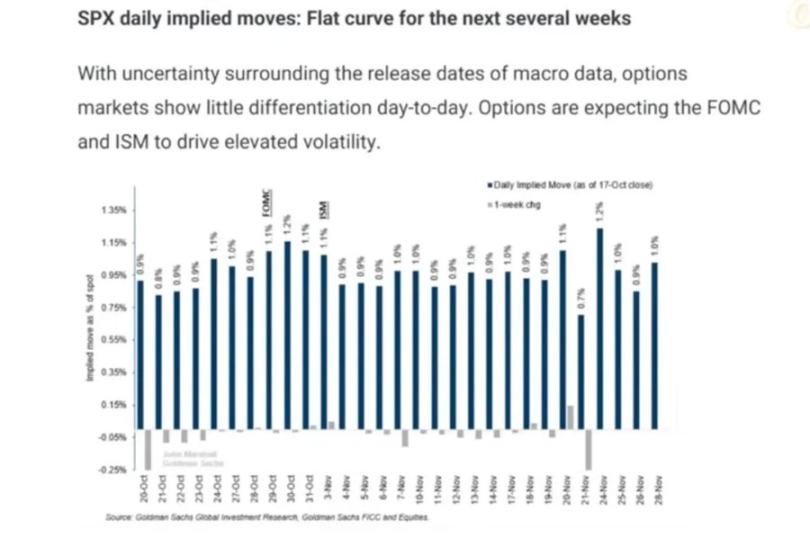

Unlike a single “Minsky moment,” this regime implies gradual erosion: declining real returns, slow de-equitization, and the management of intermittent volatility through policy intervention.

Key themes to watch:

- Public credit dominance: as deficits persist, the crowding-out effect will intensify

- Industrial reshoring: government-driven nominal growth through subsidies

- Private credit saturation: ultimately leading to margin compression and idiosyncratic defaults

- Stock market stagnation: as capital chases certainty rather than growth, P/E ratios will face a decade-long compression